10.2 Bocetos & Trailer / Sketches and Trailer

Fotos: © Morfi Jimenez, © Giancarlo Shibayama, © Dante Pineda,

© Huanchaco.

Photos: © Morfi Jimenez, © Giancarlo Shibayama, © Dante Pineda,

© Huanchaco.

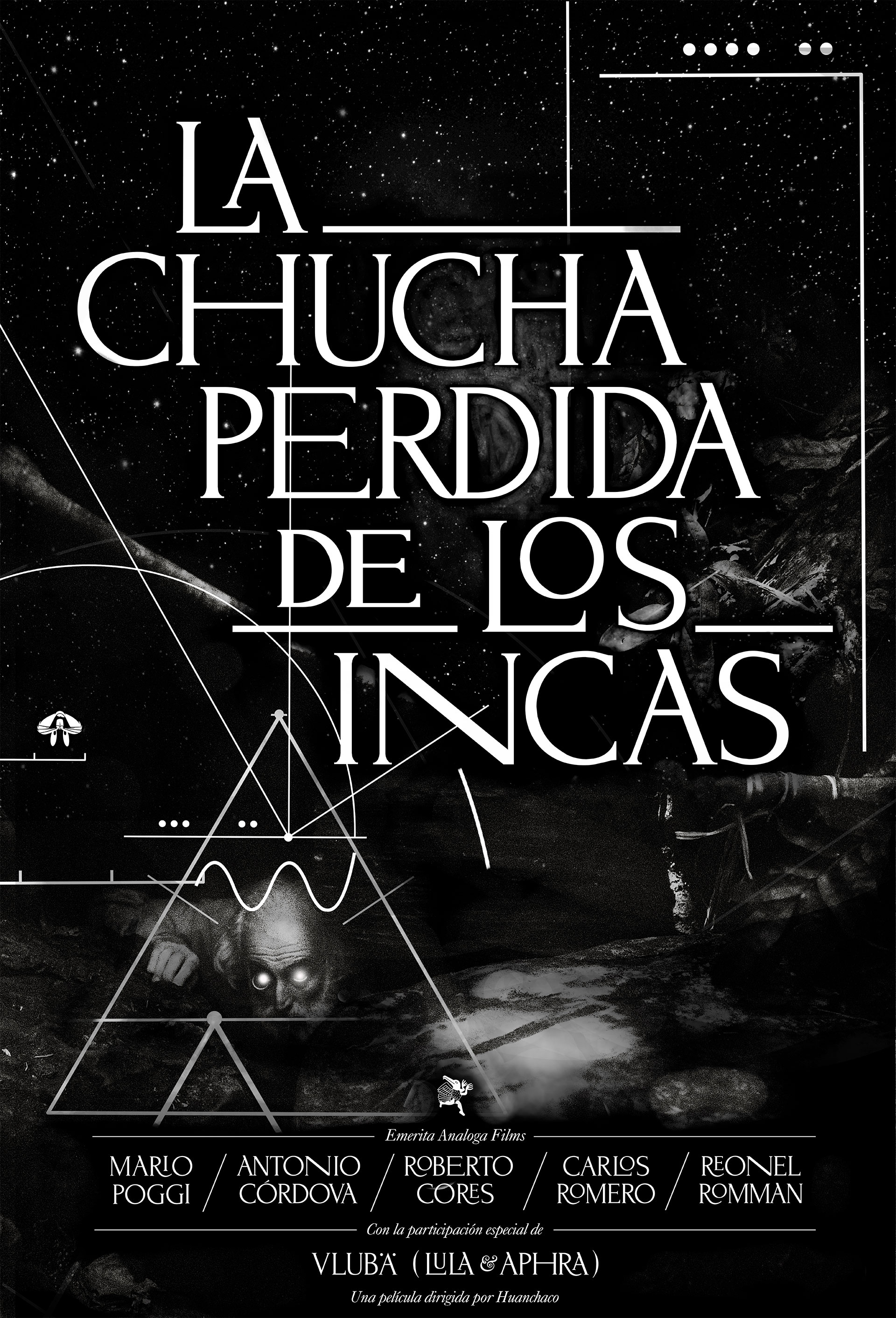

«La chucha perdida de los Incas» (2019): La búsqueda de la búsqueda

Podríamos pensar en La chucha perdida de los Incas, ópera prima del artista trujillano Fernando Gutiérrez ‘Huanchaco’, como una suerte de delirio etnográfico: la descripción densa, por ratos onírica y casi nunca lineal, de sistemas de creencias que resisten en un mundo cínico y descreído; la representación (inquisitiva, pero casi siempre amable) de sujetos que, casi como cualquiera, intentan resolver las dudas sobre la existencia a partir de sus propios medios, sobre todo mediante la fe, la pesquisa intelectual y la expresión creativa. A partir de un collage de estilos diversos, y priorizando voces que serían fácilmente censuradas en el formato mainstream, este largometraje documental, moldeado por una fervorosa curiosidad y cierta vocación al escándalo, ofrece suficientes preguntas que nos recuerdan, una vez, el poder reflexivo del cine.

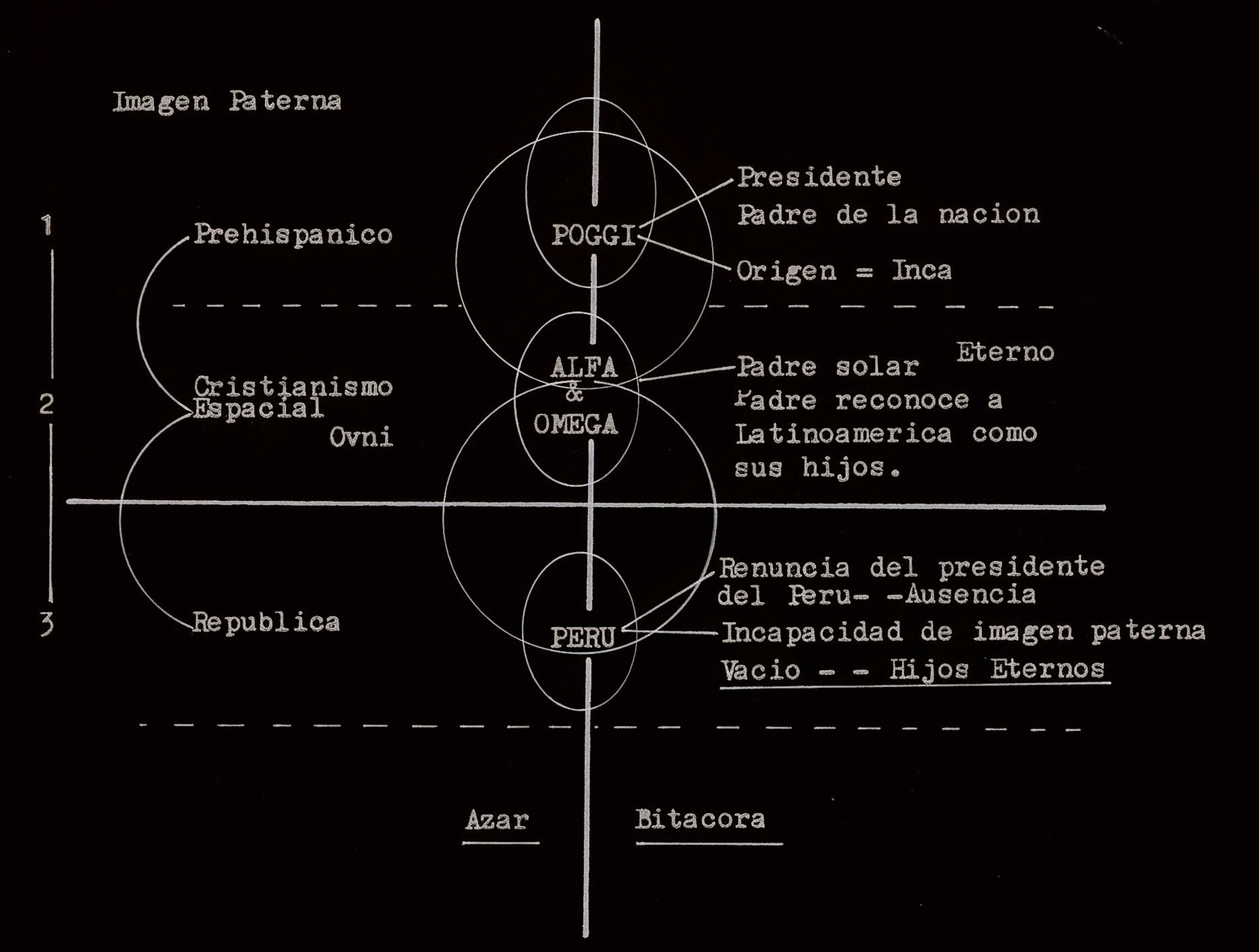

La propuesta de Huanchaco parece situarse en el video-ensayo, y su tesis, esgrimida con cierto tono melancólico en las primeras escenas del film, sostiene que existe una suerte de carencia fundamental en la sociedad peruana, que puede ser extrapolada a diferentes comunidades y sujetos en el film: existe una suerte de orfandad natural que determina al Perú, una falta de figura paterna que afecta, casi como punto medular, el tipo de creencias que asumen los individuos. La falta de padre, como una afección freudiana que se hace una ausencia dolorosísima, altera la forma en que los sujetos se aproximan a la creencia y la sociedad. Huanchaco presenta algunas comunidades (si cabe el término), cada una buscando su propia manera de suplir la carencia. La iglesia Alfa y Omega, que busca unir ideales cristianos con ufología y creencias en alienígenas. Grupos que celebran eventos ufólogos o recrean la estética de ciencia ficción en música (casi ritual), buscando contacto con lo sobrenatural. El propio cineasta está en la búsqueda, arropado por la enigmática figura de Mario.

El drama en La chucha perdida… aunque quiera girar en torno a la búsqueda de figura paterna, pero, como se evidencia en los primeros minutos del film, parece que Huanchaco y compañía ya pueden presumir una: Mario Poggi se torna en el protagonista no autorizado de la cinta, en buena medida por las evidentes contradicciones en torno a su figura y legado, así como por la apacible (uno diría hasta parsimoniosa) actitud con la que se enfrenta a su pasado y futuro. Poggi, psicoanalista y experto en distintos rituales prehispánicos, con la voz calmada y la mirada siempre fija en algún objeto de análisis, se vuelve la figura central del film: reconoce haber sido culpable de crímenes en pasado, que lo llevaron a la cárcel (donde se pasó años estudiando a presos violentos, con el evidente patrón de haber crecido sin figura paterna), y, más adelante, se volvió consejero de organizaciones estatales, artista reconocido y coleccionista. Es, sin duda, una imagen curiosa. ¿Qué implica que el “padre” del film sea, en el fondo, un ex convicto, asesino confeso y experto contratado por la policía en el Perú (además de psicólogo experimental)? Parece demostrar, una vez, el tipo de negociación que existe entre figuras de autoridad y sus seguidores (estos últimos sopesando lo dudoso o reprochable de sus líderes), las atribuciones imperfectas de la figura paterna, el fraccionamiento.

Curiosamente, La chucha perdida… se aleja de su premisa y, frente a los distintos personajes que describe, relata las extrañas implicaciones del acto de creer, sobre todo, cuando la creencia se aparta de los medios tradicionales. La necesidad de creencia implica que las figuras de autoridad (sea desde lo paternal, lo intelectual o lo religioso -y que pueden ser lo mismo) sean particularmente disruptivas, inclusive imperfectas, lo que implica, a su vez, sistemas de creencia y parentesco que funcionan artificialmente, los cuales, luego de la caída de la modernidad, hacen lo posible por tomar retazos de teorías religiosas y científicas: se generan creencias mosaico, que engloban distintos enfoques, antes percibidos como contradictorios. La Iglesia Alfa y Omega interseca ciencia y religión, astrología y teología, en la figura de un Cristo científico y unos alienígenas anunciados en la Biblia. El propio Mario Poggi recurre a mecanismos de terapia alternativa y les dota de rigor científico.

Siempre es bien recibido cuando la cámara se fija en aquellos rincones que no suelen ser vistos en el audiovisual (y en casi ningún espacio público). Huanchaco filma orgullosamente a comunidades de las periferias, académicos que no trabajan en la academia, creyentes que no son reconocidos como tales, devotos de la ciencia ficción y la ufología, entre otros. Vemos algunos patrones: las iglesias captan la atención de aquellos que necesitan ayuda rápida, transformación corporal y guía moral; la ufología nos invita a pensar en un futuro mejor y activar nuestra esperanza ante seres superiores; el tipo de psicoanálisis experimental de Poggio busca aliviar la carga emocional de las personas y forzar, a partir de la alteración neuronal, la tranquilidad. Ciencia/religión, como respuesta a la necesidad inmediata; más alivio.

El trabajo de Huanchaco consigue mitigar los evidentes excesos de su propuesta. En casos como este -cine experimental de autor- uno esperaría que, bajo la excusa de ser un proyecto personal y ajeno a estándares, reine el exceso y la autoindulgencia. Este no es el caso. Dentro del caos, parece existir alguna suerte de orden; patrones. Por un lado, La chucha perdida… parece emular el tipo de relato viajero que asumiría algún explorador que, perdido en un territorio recóndito y agreste, decide desenmarañar los significados detrás de rituales y creencias. El explorador, reflejado en la intrusiva cámara de Huanchaco, realiza la búsqueda de la búsqueda: quiere darle sentido a la búsqueda “de padre” que puede tener una sociedad en específico (inclusive un país), lo que se descompone en pequeñas búsquedas Por otro lado, el film evidentemente recurre al estilo testimonial, forzando al explorador a reconocer su propia vulnerabilidad y, por tanto, su carencia.

De alguna manera, con su film, Huanchaco parece hacer una suerte de meta-ensayo, en la medida en que su film reflexiona (a partir de la parodia y la introspección) sobre la naturaleza de la argumentación en el cine: ¿son necesarias las grandes preguntas (como la búsqueda del “padre) para que el video-ensayo cobre valor? ¿Acaso se espera que el film, así como tantos otros, pueda dar respuestas concluyentes sobre eso que cuestiona? ¿Debería haber respuestas, si quiera? Quizás por eso Huanchaco echa mano a cuanto elemento fílmico encuentre: flashbacks recreados con actores sin diálogos; secuencias animadas al acercarse el clímax; entrevistas a luz artificial y con la cámara pegada al sujeto, recreando al voyeur; videos caseros recuperados luego del tiempo; escenas que, a partir de la mirada antropológica, capturan el estado de trance de los creyentes. Por momentos, uno podría pensar que el estilo del film, dado su falta de cohesión, genere desatención. Aun así, el film, gracias a los juegos de estilo y sus personajes entrañables, perdura.

La chucha perdida de los Incas se acaba de estrenar en cines. Evidentemente, no es el tipo de propuesta para un escape de fin de semana, pero, como una suerte de bichito intelectual (que incomoda constantemente a la audiencia con sus filosas conclusiones y personajes estrafalarios), como un “gabinete de curiosidades” y disruptivos personajes, y, sobre todo, como portador de preguntas inquietantes (y necesarios), el film cumple con su objetivo. Que Huanchaco haya trabajado con cuidado su puesta en escena (y que el montaje evite el cansancio de la audiencia) solo refuerza su atractivo primario. No sabemos si los incas encontraron a su figura paterna, pero el film, con sus aciertos y excesos, ha hallado suficientes motivos para que su tesis (aunque ya no sabemos muy bien cual es) se mantenga en discusión.

Nota: La película inició su circuito de estreno alternativo este 6 de abril en el CCPUCP y en Cine Teatro Irracional, en Lima. Distribuida por Tiempo Libre (productora de Juan Daniel Fernández), el film luego se podra ver en las salas del Cine Chimú en Trujillo, Umbral Cine en Arequipa y Qine Cine en Cusco. La ruta de proyección también incluye a Sicuani, Písac y Urubamba; así como las ciudades de Huancayo, Ayacucho, Chiclayo, Puno, Ica, Iquitos y Pucallpa, durante los meses de abril y mayo.

Mauricio Jarufe

“The Lost Pussy of the Incas” (2019): The Quest for the Search

We could consider “The Lost Pussy of the Incas,” the debut film by Trujillo artist Fernando Gutierrez “Huanchaco,” as a kind of ethnographic delirium: a dense, sometimes dreamlike, and rarely linear description of belief systems that persist in a cynical and unbelieving world. It represents (inquisitively, yet mostly kindly) individuals who, like anyone else, attempt to solve existential doubts through their own means, primarily through faith, intellectual inquiry, and creative expression.

Through a collage of diverse style, and prioritizing voices that would easily be censored in mainstream format, this feature-length documentary, shaped by fervent curiosity and a certain inclination towards scandal, offers enough questions that once again remind us of the reflective power of cinema.

Huanchaco’s proposal seems to be situated within the realm of video-essay, and his thesis, presented with a certain melancholic tone in the early scenes of the film, argues that there is a fundamental lack in Peruvian society, which can be extrapolated to different communities and individuals within the film: there is a kind of inherent orphanhood that defines Peru, a lack of paternal figure that profoundly affects the types of beliefs individuals adopt. The absence of a father, akin to a Freudian affliction that becomes a painful void, alters the way individuals approach belief and society. Huanchaco presents several communities (if one can use the term), each seeking their own way to compensate for this deficiency. The Alfa and Omega Church, for instance, aims to blend Christian ideals with ufology and beliefs in extraterrestrial beings. there are groups that celebrate ufological events or recreate science fiction aesthetics in their music (almost ritualistically), seeking contact with the supernatural. The filmmaker himself is on a quest, accompanied by the enigmatic figure of Mario.

The drama in “The Lost Pussy.......” revolves around the search for a paternal figure. However, as evident in the first few minutes of the film, it seems that Huanchaco and his companions can already claim to have one: Mario Poggi becomes the unauthorized protagonist of the film, largely due to the evident contradictions surrounding his figure and legacy, as well as his calm (one might even say languid) attitude towards his past and future. Poggi, a Psychoanalyst and expert in various pre-Hispanic rituals, with his calm voice and gaze fixed on some object of analysis, become the central figures of the film. He acknowledges having been guilty of crimes in the past, which led him to prison (where he spent years studying violent inmates, with the clear pattern of having grown up without a paternal figure), and later became an advisor to state organizations, a recognized artist, and a collector. It is undoubtedly a curious image. What does it imply that the “father” of the film is, essentially, a former convict, a self-confessed murderer, and an expert hired by the police in Peru (in addition to being an experimental psychologist)? It seems to demonstrate, once again, the kind of negotiation that exists between figures of authority and their followers (the latter weighing the dubious or reproachable aspects of their leaders), the imperfect attributions of the paternal figure, and fragmentation.

Interestingly, “The Lost Pussy.......” deviates from its premise and, in the face of the different characters it portrays, it narrates the strange implications of the act of belief, especially when belief departs from traditional means. The need for belief implies that figures of authority (whether paternal, intellectual, or religious – which can be one and the same) are particularly disruptive, even imperfect. This, in turn, gives rise to belief and kinship systems that function artificially, which, after the decline of modernity, strive to incorporate fragments of religious and scientific theories: mosaic beliefs emerge, encompassing different approaches that were previously perceived as contradictory. The Alfa and O mega Church intersects science and religion, astrology and theology, in the figure of a scientific Christ and extraterrestrial foretold in the Bible. Mario Poggi himself resort to alternative therapy mechanisms and endows them with scientific rigor.

It is always welcome when the camera focuses on those corners that are not usually seen in audiovisual media (and in almost no public spaces). Huanchaco proudly films communities from the outskirts, academics who do not work in academia, believers who are not recognized as such, enthusiasts of science fiction and ufology, among other. We observe some patterns: churches capture the attention of those in need of quick help, bodily transformation, and moral guidance; ufology invites us to envision a better future and activate our hope in the face of superior beings; Poggi’s type of experimental psychoanalysis seeks to alleviate emotional burdens and, through neuronal alteration, induce tranquility. Science/religion becomes a response to immediate needs, offering further relief.

Huanchaco’s work manages to mitigate the evident excesses of his proposal. In cases like this – authorial experimental cinema – one would expect that, under the guise of being a personal project outside of standards, excess and self – indulgence would prevail. However, this is not the case. Within the chaos, there seems to be some sort of order, pattens. On one hand, “The Lost Pussy of the Incas” appears to emulate the type of travel narrative that an explorer would undertake when lost in a remote and rugged territory, deciding to unravel the meanings behind rituals and beliefs. The explorer, reflected in Huanchaco’s intrusive camera, embarks on a search for search itself: trying to make sense of the “fatherhood” quest that a specific society (even a country) may have, which breaks down into smaller quests. On the other hand, the film clearly employs testimonial style, forcing the explorer to acknowledge their own vulnerability and, consequently, their own lack.

In a way, Huanchaco’s film seems to engage in a sort of meta-essay, as it reflects (through parody and introspection) on the nature of argumentation in cinema: are big questions like the search for “fatherhood” necessary for a video-essay to have value?

Are we expecting the film, like many others, to provide conclusive answers to the questions it raises? Should there even be answers? Perhaps that’s why Huanchaco employs every filmic element he can find: recreated flashbacks with dialogue-less actors, animated sequences building up to the climax, interviews with artificial lighting and the camera close to the subject, recreating a voyeuristic perspective, recorded home videos from the past, scenes that capture the trance-like state of believers though an anthropological gaze. At times, one might think that the film’s lack of cohesion in style could lead to a lack of attention. Nevertheless, thanks to its playful stylistic approach and endearing character, the film endures.

“The Lost Pussy of the Incas” has been released in theaters. Obviously, It’s not the type of proposition for a weekend getaway, but as an intellectual curiosity (constantly unsettling the audience with its sharp conclusions and eccentric characters), as a “cabinet of curiosities” with disruptive characters, and above all, as a bearer of unsettling and necessary questions, the film fulfills its objective. The careful staging by Huanchaco and the editing that avoids audience fatigue only reinforce its primary appeal. We may not know if the Incas found their father figure, but the film, with its successes, and excesses, has found enough reasons to keep its thesis (although we’re not quite sure what it is anymore) under discussion.

Note: The film started its alternative release circuit on april 6th at CCPUCP and Cine Teatro Irracional in Lima. Distributed by Tiempo Libre (producer Juan Daniel Fernandez), the film will later be screened at Cine Chimu in Trujillo, Umbral Cine in Arequipa, and Quine Cine in Cusco. The screening route also includes Sicuani, Pisac, and Urubamba, as well the cities of Huancayo, Ayacucho, Chiclayo, Puno, Ica, Iquitos, and Pucalpa, during months of April and May.

Mauricio Jarufe

La ficción en la realidad

Decía Ricardo Piglia que no se trata de preguntarnos cómo aparece la realidad en la ficción, sino cómo funciona la ficción en la realidad. Es una idea precisa para pensar el documental La chucha perdida de los Incas (2019) dirigido por el artista Fernando Gutiérrez “Huanchaco”, actualmente presentándose en varias ciudades del país. La película parte del vínculo entre el artista y el controvertido personaje Mario Poggi, quien le sugiere a Huanchaco que vaya en busca de la piedra con forma de vagina aludida en el título. Frente a la arqueología oficial que desmerece la idea de que, en el pasado, hubiera existido un espacio ritual importante de esas características, Poggi sostiene que funcionaba como un lugar de sanación para problemas de fertilidad y que tenía su correlato en otra roca fálica en los Andes del sur. El artista y psicólogo conoció “la chucha” tras salir de prisión, a inicios de los años 1990, cuando pasó una temporada en la Selva Central y unos amigos Asháninka le mostraron el lugar, poco después de los terribles sucesos que lo llevaron a ser una figura polémica en la cultura de masas local.

Frente a lo que usualmente sería tomado como un delirio más del señor de pelo verde que ofrecía servicios psicoterapéuticos en el Parque Kennedy, Huanchaco opta por seguirle la pista y organizar una expedición en busca de la piedra. Y la encuentra. Pero la historia da un giro cuando Poggi muere y su compañera recibe un enigmático mensaje por parte de seres extraterrestres frente al mar de Chorrillos, y Huanchaco lo lleva a un local de Alfa & Omega (A&O) para descifrarlo. De ahí en más, la película combina la historia de la búsqueda y hallazgo de “la chucha” con una indagación en el comunismo cósmico de A&O, en sus espacios y rituales, así como en la figura del Hermano Antonio Córdova, Depositario de la Divina Ciencia Celeste y principal promotor del culto en el país desde los años 1970. Vemos los rollos que contienen la doctrina de A&O, conocemos sus hábitos de alimentación y entramos en un peculiar ritual en la playa de Chilca. En medio de ello, el Hermano Antonio fallece.

Dos muertes atraviesan el rodaje del filme y Huanchaco las articula a través de una pregunta por el lugar de la figura paterna en la conformación de la nación peruana. Como lo plantea al inicio, en una secuencia autobiográfica, el artista busca un padre y encuentra dos personajes que, de distintos modos, cumplen aquella función: mientras que Poggi ofrece terapias de color para encontrar al padre psíquico mediante curiosos aparatos diseñados por él mismo, el Hermano Antonio funge como articulador de un movimiento colectivo, es el medio para entrar en contacto con la divinidad. Ambos se ocupan de instalar una fe en el cuerpo social, aunque desde posiciones distintas y en buena medida contrapuestas. Sin embargo, Huanchaco parece haber encontrado en ambos algo que le concierne, un modo de relacionar preguntas subjetivas sobre su vida con una suerte de interés en algo así como el destino nacional, sobre todo en el contexto de la llamada “crisis política” que ha llevado a la rápida sucesión de presidentes en los últimos años. Figuras paternas, plantea el artista, y acaso su filme parece indicar que la posibilidad de orientarse en el mundo contemporáneo no se encuentra en la arena política oficial, sino en las variadas formas en que, desde abajo —desde el debajo de los movimientos sociales, pero también desde el debajo de la criminalidad, la locura y el estigma—, la sociedad lucha por hacer sentido del presente.

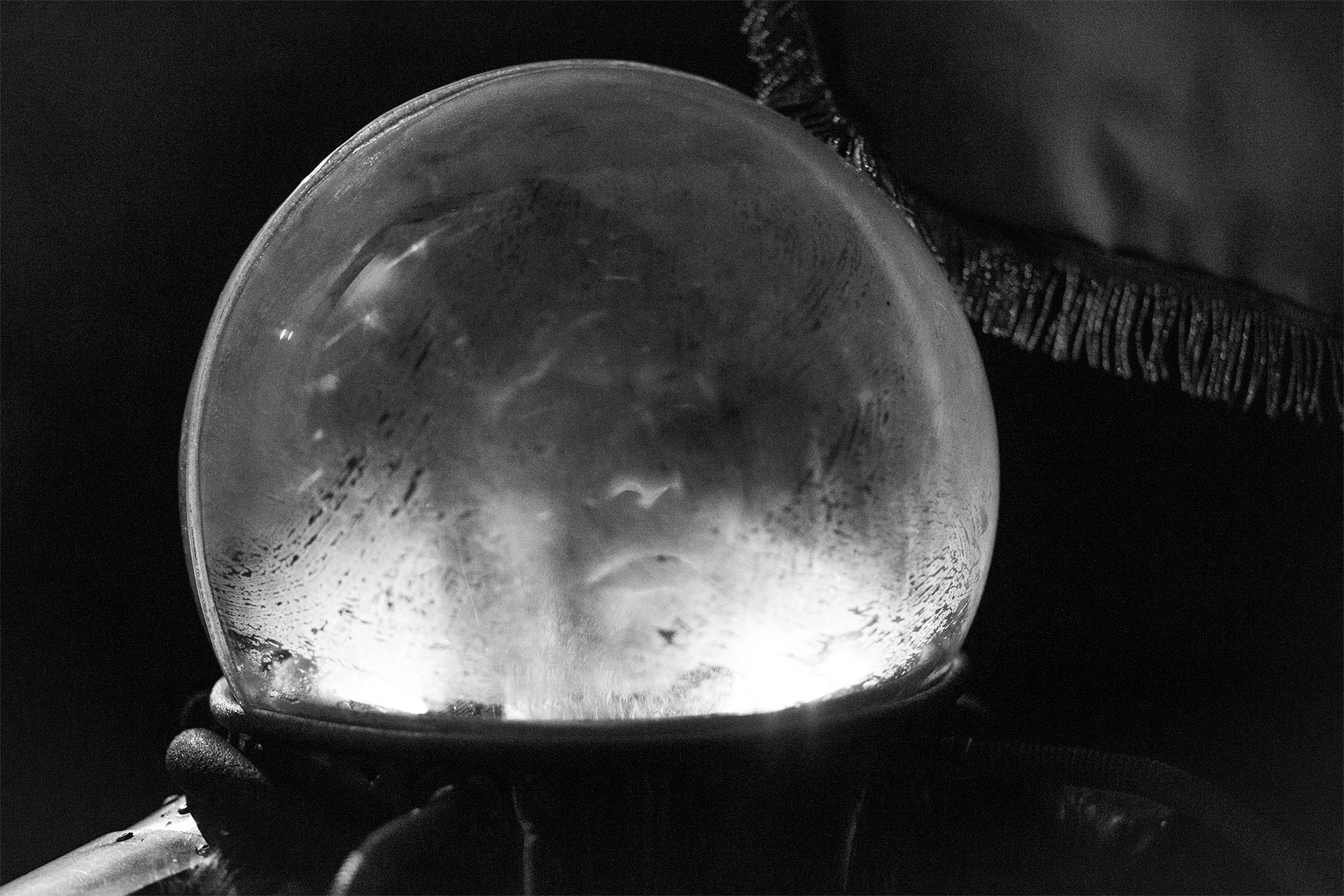

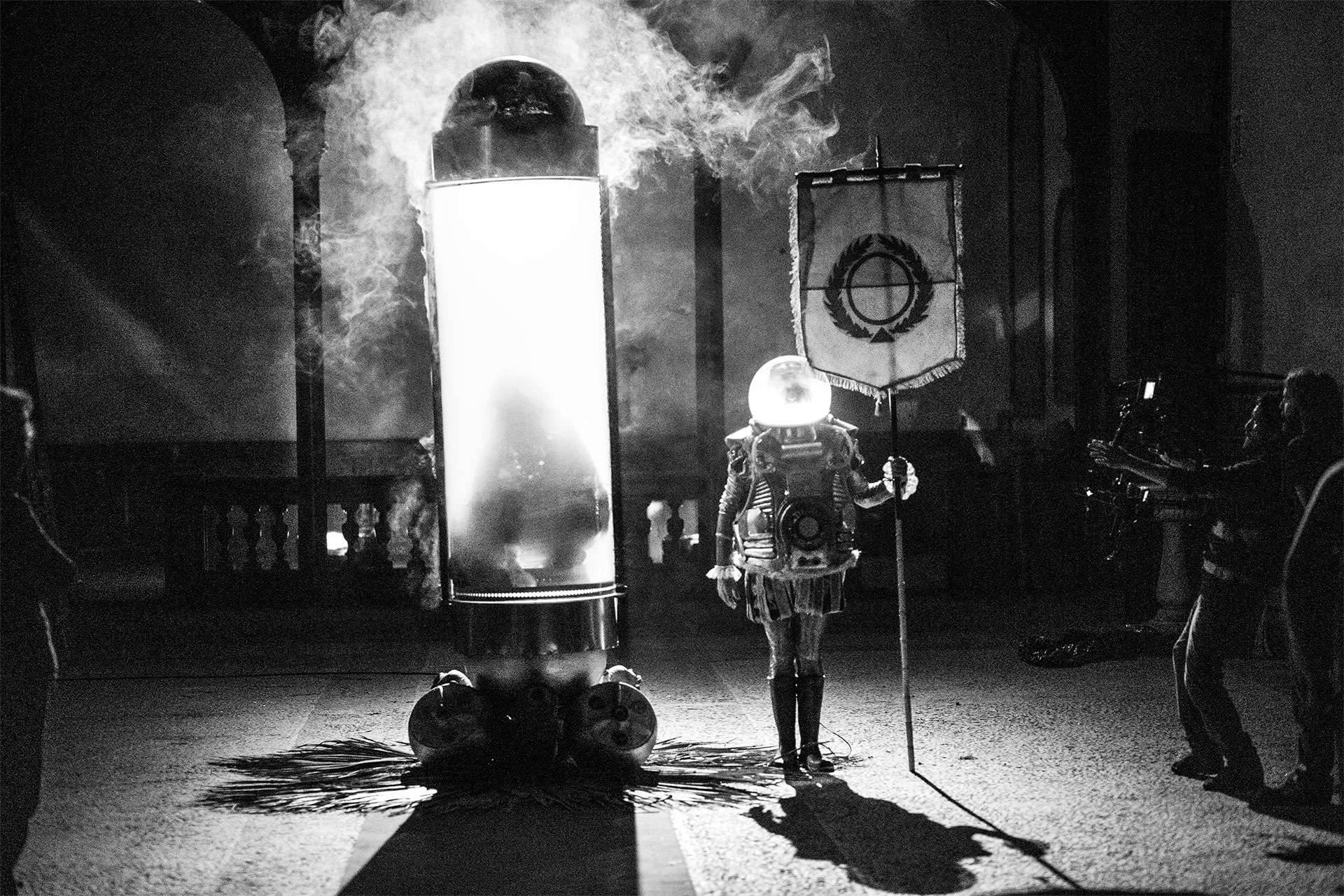

Hacia el final, La chucha perdida de los Incas llega a una suerte de triple clímax. Primero, el concierto-ritual para contactar a Cristo y su comunidad extraterrestre en medio de la oscura playa de Chilca muestra un despliegue de recursos estéticos donde la música y la ambientación a cargo de Huanchaco configuran un escenario futurista que amplifica los rituales cotidianos de A&O. Luego, la cueva donde está “la chucha” reaparece como escenario de un ritual en el que vemos a varios personajes del documental ataviados con cascos y prendas diseñadas por Huanchaco, como parte de su proyecto Civilización Atalaya, que presentó en el Museo de Arte Contemporáneo-MAC el 2021. En ambos casos, el artista ha construido escenas que plantean una continuidad notable con su obra pictórica, gráfica e instalativa, que dio a conocer en sucesivas entregas desde el 2018 hasta el presente —todas vinculadas al proyecto de la película, como pequeñas muestras del proceso de investigación y producción del artista—. Finalmente, el último clímax proviene de las vistas de protestas en el Centro de Lima, donde usualmente encontramos a los A&O profesando su doctrina y haciendo cuerpo con otros movimientos sociales, tras el indulto a Alberto Fujimori otorgado por PPK poco antes de renunciar a la presidencia. Dos días después de la muerte del Hermano Córdova, entonces, la realidad hizo lo suyo para que estas dos historias se encuentren. Dos ficciones que operan en nuestra realidad y plantean distintos modos de lidiar con las contradicciones que vivimos.

Mijail Mitrovic

Fiction in reality

Ricardo Piglia used to say that it’s not about asking how reality appears in fiction, but how fiction works in reality. This is a precise idea to consider in the documentary film “The Lost Pussy of the Incas” (2019), directed by artist Fernando Gutierrez “Huanchaco,” currently being in various cities in the country. The film revolves around the relationship between the artist and the controversial character Mario Poggi, who suggest to Huanchaco that he should search for the vagina-shaped stone mentioned in the title. in the face of official archeology that undermines the idea of the existence of such an important ritual space in the past, Poggi maintains that it served as a healing place for fertility issues and had its counterpart in another phallic rock in the southern Andes. The artist and psychologist encountered “The Pussy” after his release from prison in the early 1990s when he spent time in the Central Selva, and Ashaninka friends showed him the place, shortly after the terrible events that made him a controversial figure in the local mass culture.

In the face of what would usually be dismissed as just another delusion from the green-haired man offering psychotherapeutic services in Kennedy Park, Huanchaco chooses to follow the trail and organizes an expedition in search of the stone. And he finds it. But the story takes a twist when Poggi dies, and his partner receives an enigmatic message from extraterrestrial beings by the sea in Chorrillos. Huanchaco takes it to an Alfa & Omega (A&O) location to decipher it. From then on, the film combines the story of the search and discovery of “The Pussy” with an exploration of A&O’s cosmic communism, its space and rituals, as well as the figure of Brother Antonio Cordova, Custodian of the Divine Celestial Science and the main prometer of thecult in the country since the 1970s. We see the scrolls containing A&0’s doctrine, learn about their eating habits, and enter a peculiar ritual on the beach of Chilca. In the midst of it all, Antonio passed away.

Two deaths permeate the filming of the movie, and Huanchaco connects them through a question about the role of the father figure in shaping the Peruvian nation. As stated at the beginning, in an autobiographical sequence, the artist seeks a father figure and encounters two characters who, in different ways, fulfill that role: while Poggi offers color therapies to find the psychic father through curious devices designed by himself, Brother Antonio serves as the facilitator of a collective movement, the means to connect with divinity. Both of them aim to instill faith in the social body, albeit from different and often opposing positions. However, Huanchaco seems to have found something concerning in both of them, a way to relate subjective questions about his own life to a sort of interest in the national destiny, particularly in the context of the so-called "political crisis" that has led to the rapid succession of presidents in recent years. The artist proposes paternal figures, and perhaps his film suggests that the possibility of finding direction in the contemporary world lies not in official political arenas, but in the various forms in which society, from below—through social movements, but also through crime, madness, and stigma—struggles to make sense of the present.

Towards the end, "La chucha perdida de los Incas" reaches a sort of triple climax. First, the concert-ritual to contact Christ and his extraterrestrial community on the dark beach of Chilca showcases a display of aesthetic resources where the music and atmosphere, led by Huanchaco, create a futuristic stage that amplifies the daily rituals of A&O. Then, the cave where "la chucha" is located reappears as the setting for a ritual, where we see various characters from the documentary adorned with helmets and garments designed by Huanchaco as part of his project Civilización Atalaya, which he presented at the Museum of Contemporary Art-MAC in 2021. In both cases, the artist has constructed scenes that exhibit a notable continuity with his painting, graphics, and installation work, which he has been showcasing in successive exhibitions since 2018 to the present, all of which are linked to the film project as small samples of the artist's research and production process. Finally, the last climax comes from the footage of protests in downtown Lima, where we usually find A&O professing their doctrine and joining other social movements, following Alberto Fujimori's pardon granted by PPK shortly before resigning from the presidency. Two days after Brother Córdova's death, reality played its part in bringing these two stories together. Two fictions that operate within our reality and present different ways of dealing with the contradictions we experience.

Mijail Mitrovic

Su región en Identidad Paterna, Crisis y Trascendencia en el Cine Peruano a través de 'La Chucha Perdida de los Incas'

La Chucha Perdida de Los Incas (, Perú, 2019) es una película documental dirigida por Fernando Gutierrez, también conocido como Huanchaco. Esta obra cinematográfica, de tan solo 80 minutos navega entre la no ficción y la performance, explorando la identidad y planteando preguntas como "¿quiénes somos?" y "¿quién soy?". La película se sumerge en la figura polémica e impresionante de Mario Poggi, quien junto con Huanchaco, se adentra en la búsqueda de la identidad paterna en la sociedad peruana. Esta película presenta una experiencia cinematográfica que va más allá de la narrativa tradicional y se sumerge en la exploración profunda de la identidad. La trama que presenta es una nueva propuesta que abre espacio para la reflexión y el diálogo sobre temas fundamentales en la sociedad contemporánea. Huanchaco y Poggi, estructuran la misma película en sus personajes. Huanchaco plantea las preguntas que Poggi intentará responder. En ese sentido, si observamos la película en el código de la búsqueda paterna, Huanchaco va hacia Poggi quién tiene métodos, propuestas, cuentos, mapas, sueños e ideas y todas sirven para responder algo en la realidad. Ambos tienen la capacidad de desafiar las ideas preconcebidas y las convenciones sociales, estimulando la reflexión y la búsqueda personal. A través de su exploración, la película invita a los espectadores a cuestionar sus propias identidades y a reflexionar sobre la importancia de comprender quiénes somos.

Así comenzamos un viaje fascinante de artistas. Vemos como Mario Poggi manifiesta, en un video de archivo, que siente la obligación de poner el valor humano y el ser humano en primer lugar, antes que cualquier otra consideración. Esta valiosísima idea refuerza la importancia de la identidad personal y colectiva, y establece una conexión profunda entre el arte, la sociedad y los valores fundamentales que deben prevalecer en cualquier transformación social. Una afirmación en apariencia idealista, que Poggi irá revelando su imaginación poderosa, flexible y extremadamente diversa a través de muchas intervenciones posteriores a lo largo de su vida.

En esta búsqueda, somos participantes activos una vez más del lenguaje autoral de Huanchaco, artista multidisciplinario que trasciende el lenguaje cinematográfico con su peculiar ímpetu de inocencia. Como quien descubre objetos, palabras y tesoros, él se transforma y vive en la película. A medida que avanzamos en el documental, nos enfrentamos al fallecimiento de Mario Poggi, un suceso que nos acerca a la doctrina de Alfa y Omega. En este contexto, se nos presenta al Hermano Antonio Córdova Quezada, un peruano contactado que ejerce la figura paterna y defiende su doctrina basada en la fe, llegando incluso a afirmar que "hasta la fantasía es una realidad en la creación de Dios". Aportando una capa más de significado a la pregunta inicial ¿de dónde venimos?

Para sumergirnos en La Chucha Perdida de Los Incas, es importante destacar el paralelismo existente entre la línea documental que sigue a Mario Poggi y la representación simbólica de las ideas a través de la búsqueda de la chucha perdida, en la que Huanchaco se convierte en protagonista. De manera paralela a la trama del documental, Huanchaco emprende un viaje de exploración por las cuevas de la selva en busca de este enigmático objeto. Este juego de reflejos entre las ideas expresadas y las representadas es un aspecto divergente de la película que pone a prueba el género y tensa la exploración documental. Se emplea animación, efectos visuales y una puesta en escena ficticia, plástica y desbordante. Por ello, para cuestionar la realización, es importante sondear la experiencia documental, de registro, de performance y exploración investigativa que Huanchaco ha realizado en proyectos anteriores. Aunque no es indispensable, es necesario tener curiosidad y disposición para interpretar las imágenes, los diferentes formatos utilizados, el montaje, la música y captar el subtexto que revela el ADN del autor y la amplia gama de formas que amalgama en todos sus proyectos.

Se percibe un fuerte concepto de exploración, disciplina y trabajo en torno al arte, así como una comprensión de la experiencia estética y su función dentro de la sociedad. Solo de esta manera nos atrevemos a afirmar que La Chucha Perdida de Los Incas es un buen ejemplo de toda esa investigación llevada al lenguaje cinematográfico. La película invita a sumergirse en la profundidad de su tesis, exigiendo una mirada atenta y abierta a los ricos niveles de significado que se entrelazan en su narrativa visual y conceptual.

Jaime Pinto

Their role in "Fatherhood Identity, Crisis, and Transcendence in Peruvian Cinema through 'La Chucha Perdida de los Incas'"

"La Chucha Perdida de Los Incas" (Peru, 2019) is a documentary film directed by Fernando Gutierrez, also known as Huanchaco. This cinematic work, with a runtime of just 80 minutes, navigates between non-fiction and performance, exploring identity and posing questions like "who are we?" and "who am I?". The film delves into the controversial and awe-inspiring figure of Mario Poggi, who, along with Huanchaco, embarks on a search for paternal identity in Peruvian society.

This film presents a cinematic experience that goes beyond traditional narrative and delves into a profound exploration of identity. The plot it presents is a fresh proposition that opens up space for reflection and dialogue on fundamental themes in contemporary society. Huanchaco and Poggi structure the same film through their respective characters. Huanchaco poses the questions that Poggi attempts to answer. In that sense, if we observe the film through the lens of the search for paternal identity, Huanchaco moves towards Poggi, who possesses methods, proposals, tales, maps, dreams, and ideas, all serving to respond to something in reality. Both have the ability to challenge preconceived notions and social conventions, stimulating reflection and personal exploration. Through their exploration, the film invites viewers to question their own identities and reflect on the importance of understanding who we are.

And so, we embark on a fascinating journey of artists. We witness Mario Poggi expressing, in archival footage, his sense of obligation to prioritize human value and the human being above all other considerations. This invaluable idea reinforces the importance of personal and collective identity and establishes a deep connection between art, society, and the fundamental values that should prevail in any social transformation. It's an idealistic statement that Poggi gradually unveils through his powerful, flexible, and incredibly diverse imagination in numerous subsequent interventions throughout his life.

In this quest, we once again become active participants in Huanchaco's authorial language, a multidisciplinary artist who transcends the cinematic language with his unique spirit of innocence. Like someone discovering objects, words, and treasures, he transforms and lives within the film. As we progress through the documentary, we encounter the passing of Mario Poggi, an event that brings us closer to the doctrine of Alfa and Omega. In this context, we are introduced to Brother Antonio Córdova Quezada, a contactee from Peru who assumes the role of a father figure and defends his doctrine based on faith, even asserting that "even fantasy is a reality in God's creation." This adds another layer of meaning to the initial question of "where do we come from?"

To delve into "La Chucha Perdida de los Incas," it is important to highlight the parallelism between the documentary line following Mario Poggi and the symbolic representation of ideas through the search for the lost "chucha," in which Huanchaco becomes the protagonist. In parallel to the documentary plot, Huanchaco embarks on an exploratory journey through the jungle caves in search of this enigmatic object. This interplay between expressed and represented ideas is a divergent aspect of the film that tests the genre and stretches the boundaries of documentary exploration. Animation, visual effects, and a fictional, artistic, and overflowing staging are employed. Therefore, to question the realization, it is important to delve into the documentary experience, recording, performance, and investigative exploration that Huanchaco has undertaken in previous projects. While not essential, curiosity and openness to interpreting the images, different formats used, editing, music, and capturing the subtext that reveals the author's DNA and the wide range of forms amalgamated in all his projects are necessary.

A strong concept of exploration, discipline, and work in relation to art is perceived, as well as an understanding of aesthetic experience and its function within society. It is only in this way that we dare to affirm that "La Chucha Perdida de Los Incas" is a good example of all that research translated into the cinematic language. The film invites us to immerse ourselves in the depths of its thesis, demanding a attentive and open gaze to the rich levels of meaning intertwined in its visual and conceptual narrative.

Jaime Pinto